“Keep your heads down, girls,” Betty’s voice called from the back of the van. “There are men with machine guns out there.”

The van crawled to a stop.

Some girls heeded Betty’s advice, shrinking down into the cracked vinyl of the seats and trying their best to disappear. Others, like me, sat up to peer through the grimy windows, wanting to glimpse the action.

The group of Brazilian men approaching our van were, in fact, all toting machine guns. They held them casually, too comfortably, guns dangling from their hands like an extension of their limbs. It was strangely beautiful, the ease with which they handled something so deadly. Our driver rolled down his window and said something to them in Portuguese. They answered him, quick and sharp. What are they saying?Inside the van, I felt the blood burn hot in my veins.

Am I seriously about to die?

Suddenly, the van lurched forward and sent us tumbling back into our seats. The men and their guns faded away in the rearview mirror, swallowed by a cloud of dry, terracotta dust stirred up in the wake of the van’s tires. We continued on into the heart of the favela.

favela, [ fuh-vel-uh; Portuguese fah-ve-lah ]

noun

a shantytown in or near a city, especially in Brazil; slum area

A few months before we arrived, an American couple visiting Rio de Janeiro got lost on their way to the airport. They pulled off the highway, into the heart of a favela, and were stopped by men with guns. When a man peered into the window and saw two white Americans, he pulled the gun from his hip and shot and killed them both.

They were on their honeymoon.

The streets of a favela were a labyrinth of stone and metal, dirt and concrete, everything covered with a thick film of grime.

A dark river of dirt cut through it all, and on this road, our van bumped along.

Houses made of scrap sheet metal leaned precariously up against one another, missing roofs and windows and walls. Wild dogs ran in the street. Men lounged outside of rundown stores, clouds of smoke hanging in the air around them, guns laid casually across their laps. Children roamed freely, their bare feet black with dirt, running alongside our van as we passed. Trash covered the hillsides—heaped so high and thick that you couldn’t see the ground—and wild pigs rooted in it. Later, we would learn that this was where the children would go to play. On every rooftop, there were big blue tubs that looked like kitty pools.

“For rainwater,” Betty informed us.

Silence.

What about the houses that don’t have a roof?

And there were many of them.

What do they do for water?

It was August of 2018 and I was a rising college sophomore, swimming through that stage of life where a girl is doing her best to become a woman. I was a student at Belmont University, playing basketball and studying English. My responsibilities as a student-athlete seemed colossal and all-encompassing.

I was wrong, of course. But I would learn that soon enough.

Two women led my team’s mission trip to Rio: the first being the before-mentioned Betty; a white-haired, graceful saint of a woman in her seventies who founded the Women’s Basketball program at Belmont University. Betty is all snark and laughter and humility, a pillar of light wherever she goes. She speaks gently, choosing her words with careful intention, and she loves to dance.

The second woman was Sharon, a woman who dedicated her life to helping the impoverished natives of Rio. Sharon is all bark and sharp edges and deep, maroon hair. She is fluent in Portuguese, loud and intimidating, and walks into every room as if she owns it. They evened each other out perfectly.

We were venturing into territory that only an absurdly small number of Americans would ever set eyes on. Most of them would be killed on the spot. The only reason we were allowed access into the favelas was this: Sharon had a strong connection with a pastor in one of Rio’s most dangerous favelas. This pastor was highly renowned throughout the community because he took children into the church, offering them free meals, education, safety, love, and acceptance. Basically, the drug lords loved to send their kids to church because it meant there was hope for them outside of the drug cartels.

An image: one of those machine-gun-toting men, one hand wrapped around the butt of his gun, an unforgiving extension of his arm, and the other clutching a child to his leg, a merciful extension of his soul. There is blood on this man’s hands, and he uses those same hands to smooth the dark hair away from his child’s forehead. “Go to church,” he says, kissing his child on the head. “And come tell me what you learned.” And that night when they reconvene, in a house that may or may not have a roof and four walls, the man listens intently as his child talks about his day at the church, eager and excited, radiating joy as he speaks of a Savior who loves and forgives. A Savior who flips tables in anger. A Savior who cries blood from fear. But nevertheless, a Savior who rises from the dead.

So there we were, fifteen American college girls, cruising into a literal Brazilian war zone in a dingy, unmarked white van while Portuguese rap looped over the radio and men with machine guns peered into our van.

It was a moment, if you know what I mean—one of those moments where you sit back on your heels and look at the bird’s eye view of your life and all you can think is what the hell is going on?

Yeah. One of those.

I eventually learned that not all these children were lucky enough to be sent away to church. Not all of these children were lucky enough to hear the speech that Betty always gave in the schools we visited: when I look at you all, I see doctors, lawyers, surgeons, and artists….

One afternoon, I was playing soccer with a young boy. He was about seven years old, and the only familiar language we both spoke was sports. At one point, I crouched down to give him a high-five, and we looked at one another eye-to-eye. His little eyes drifted down to my neck and rested on the gold cross necklace that lay there. Little dark eyes, wide with fascination. Little dark fingers, reaching out to gently touch the gold as it glinted white in the sunlight. I smiled and began to fumble with the hook. Before I could give it to him, one of our translators rushed over and snapped at the boy in Portuguese. The boy, a sudden ball of anger, snapped back just as quickly before stalking away with a twisted frown.

“Don’t show that to anyone,” the translator instructed me. His voice was stern, but his eyes were gentle. “The boy wants to sell it for drugs.”

One morning, Betty announced she needed four volunteers to go door-to-door and pray for people in their homes.

My hand shot up.

We had yet to go into the favela. We visited schools and orphanages, we walked the streets, but we had never gone up into the hills where most of the community lived. Down in the streets, people were friendly and smiling, running up to greet us. Bom-dia! Hello! Up there in the hills, it was different. Everything eerie and sour, an entire community ravaged by drugs, poverty, sickness, anger, hatred, bitterness.

But Jesus did not come for the righteous.

“No pictures,” Betty instructed. “Don’t even touch your phone. Keep it in your bag. Honestly, don’t even bring it. They won’t hesitate to shoot if they see you using it.”

And just like that, we ascended into the hills.

The further we trekked, the darker it became. It was damp—all stone and cracked concrete, no grass to soak up the water—and the makeshift houses blocked out any semblance of sunlight. Rivulets of dirty water trickled past our feet. The effect was that of some misshapen, upside-down New York City. Narrow concrete alleyways, rotting wooden doors, gaping open holes in the sides of shanties that acted as windows. Inside, five to six cots on the floor. The dark shapes of people lying, unmoving, in the shadows.

And then Sharon announcing, “I think this is it.”

We arrived at a low concrete building where four men sat on the ground by the door, cradling guns in their laps (a sight I had become surprisingly used to) and passing small bags of powder between one another. Admittedly, I was uncomfortable. A group of young American women in a foreign country perusing around drug deals? Chum for the sharks.

Sharon knocked on the door, calling out a woman’s name. No answer. After a few minutes of banging on the door, one of the men stood up. His skin was deeply tanned from the sun and there were wrinkles at the corners of his eyes. He was smoking a joint that encased us all in a cloud of sickly-sweet smoke. There was a gun strapped to his hip. When he approached us, speaking to Sharon in Portuguese, his voice was kind. After a few exchanges, Sharon thanked them and motioned us to keep moving.

“She doesn’t live here anymore,” she explained. “She lives up here, just over this hill.” After a moment’s pause, she added, “They told us to be careful.”

I looked over my shoulder at the group of men, who all raised their hands in farewell.

Up and up and up. Stair after stair.

Betty, leaning against a concrete wall to catch her breath. Finally, we reached a doorway in a small, covered alleyway. It was the middle of the day, but so dark that it could have been the middle of the night.

A woman sat on the ground outside the door, clutching a newborn baby. She was painfully thin, her skin stretched tight over protruding ribs and sharp anklebones. Even in the incredible absence of light I could make out the drug-induced glassiness of her eyes. She was riddled with sickness, her shoulders slumped forward, the pointed wings of her shoulder-blades stretching outwards as if to take flight. As we approached her, she did not speak. There on the ground, she groaned and writhed in pain, her head lolling back and forth as if she was barely conscious.

“Who wants to pray for this woman?” Betty asked quietly.

Silence. In that moment, I believe we all felt too inadequate.

Without hesitation, Betty reached out and cupped her hands gently around the woman’s face. We quickly followed, placing our hands on her shoulders, her arms, the top of her head.

“Look at me,” Betty said tenderly, and the woman did. Betty smiled—like the sun breaking through clouds—and began to pray aloud.

When Jesus walked the earth, he healed lepers with a simple touch. And when he did, he touched the lepers before he cleansed them. He did not wait for the sick to be clean in order to touch them. Thousands of years later, in a rotting, decaying alleyway in the slums of South America, I saw Jesus again, alive in the certainty of Betty’s touch.

After we left, Betty pulled us aside. We were a small group of white, female foreigners—dirt-streaked and shell-shocked, wildly out of place, the significance of everything dumbing us into silence.

“That woman is dying,” she announced, her mouth turned down with grief. “Don’t forget what you’ve seen here today.”

Only minutes after we had returned to the others, the sick woman re-appeared in our midst with tears cutting through the dirt on her cheeks. She spoke to Sharon in wild, frantic Portuguese, and suddenly turned to thrust her baby into my arms.

“She wants us to pray for her child,” Sharon translated. So we did. I was glad it was me, holding him in my arms—this squirming, dirty, gorgeous little child—and we prayed over his future while his mother sobbed breathlessly behind us.

When we were done, I slid the boy back into her arms and she caught hold of my wrist.

In that moment, she spoke quickly, animatedly, the vowels and consonants rolling off her tongue as she told me something important despite the fact we could not understand one another. The only thing I could do was hold her eye contact, let her know that I was there in that moment with her. I’ll never forget her eyes. They were bottomless pools, dark as olive pits.

When she was done saying whatever she needed to say, she kissed me firmly on the cheek and ascended back into the shadowed hillside from which she had come, her child held against her frail chest and a joint dangling loosely from her skeletal fingers.

Oddly enough, the most difficult part of experiencing these Brazilian slums was leaving.

The children hung onto our clothes, sobbing, begging us not to go in words we could not discern. Love is the most universal language we have. I saw it then for the first time—really saw it. How heartless it made me feel—how cruel and insensitive—to pry their little fingers from my shirt as I climbed back into the van.

Especially a boy of about 12. Lucas.

Lucas spoke a little English, which was how I got to know him better than the other children. He had been a part of things that I could never dream of, and it showed in the deep well of his childlike eyes. Wisdom was etched into the creases of his youth. Pure, clean joy emerged from his dirty smile. As I hugged him goodbye before I got into the van, he reached up and unabashedly wiped the tears from my cheeks with his little-boy hands.

“Do not cry,” he said firmly, his own eyes brimming with tears. The English words were staccato and clunky in the beautiful lilt of his accent. “I will see you again in the name of Jesus.”

Lucas, a skinny, snaggle-toothed, adolescent boy living in one of the most impoverished areas in the world, was reminding me of the promises of our Messiah.

And then—reverse culture shock.

Shopping bags and billboards and neon blinking signs. Homework and syllabi and ballpoint ink pens. Beer in red plastic cups, downtown streets, and do you think you can split the Uber with me because I don’t have a lot of money in my account right now?

Nothing felt the same after that. Everything was wrong. While I was in Nashville fretting over a paper’s word count, a 7-year-old boy was being used to smuggle drugs in Rio de Janeiro.

Which one of those is “the real world?” Who is being fooled here?

As the months went on, I ached for this place I had once been so fearful of.

Snatches of memory:

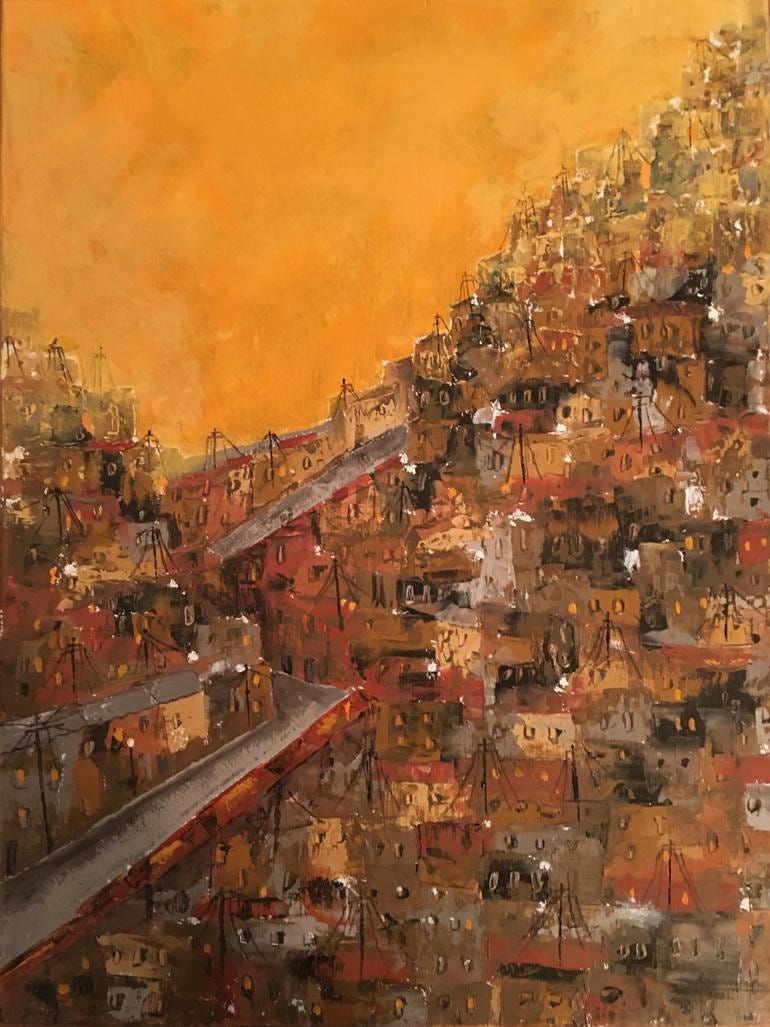

A makeshift stand where an old man, leathered and smiling, sells fresh coconuts and mangoes. A child crouching in the street, coaxing a dog to eat from his hand. A game of soccer where teenagers play sans shoes on a slab of concrete, gasping with uncontrollable laughter. Children folding themselves easily into my arms, dark eyes brimming with hope and trust. The faded wash of buildings, vibrant in the light of a Brazilian sunset—terracotta and saffron and clay.

Oftentimes, I fantasize that I am back there, in that place I previously considered poor and dirty, unsafe and treacherous. A place people only want to leave. But in my mind, I peel back the layers of these city streets and replace them with the dirt roads of a favela, where children run barefoot and call excitedly to one another. Where Lucas is still a young boy with crooked teeth. Where shadows swallow up the sick woman with her child and her joint. They are all there, stuck in the everlasting purgatory of my memory.

But the truth is this:

There is no purgatory. They are all moving forward, every last one of them, growing older, feeling joy and pain. They are carrying on. Much like you and me. And they certainly are not waiting for us to come and save them. Someone did that long ago.

Such an immersive ride. The details were so vivid. I couldn't stop reading and hope you'll reprise these personal etudes again.

This is beautiful